Armchair America: Alaska through Books

November 24, 2014

I am continuing my project of visiting all 50 states through books with a peek at Alaska. I have actually traveled to Alaska twice, once on a cruise from Whittier to Vancouver, B.C. and once traveling the roads in a rented RV with my husband, brother, and sister-in-law. I never felt far from true wilderness. Alaska seemed far wilder than any national park I’ve visited in the Lower 48, like Yellowstone or Glacier, perhaps because of all the wildlife — including large mammals like moose and bears — that we encountered while we were out and about our daily rounds. I would love to go back.

I solicited recommendations for books that captured the spirit of Alaska from a reference librarian at the Anchorage Public Libraries. Here are the titles he suggested:

- for nonfiction: Coming Into the Country by John McPhee and Aunt Phil’s Trunk, vol. 1 by Phyllis Downing Carles

- for adult fiction: The Woman Who Married a Bear by John Straley

- for juvenile fiction: The Trap by John Smelcer

- for photography: Hidden Alaska, Bristol Bay and Beyond by Michael Melford

- for Native art: Raven Travelling, Two Centuries of Haida Art

Here are the books I actually read in my armchair travels to Alaska:

Travels in Alaska by John Muir. This book recounts three of Muir’s trips to Alaska, his first in 1879, his second in 1880, and his third trip a decade later in 1890. He says: “To the lover of pure wilderness Alaska is one of the most wonderful countries in the world.” The book was written by Muir from his travel notes and sketches. It is filled with poetic descriptions of the land and the people of Alaska’s Inside Passage to Glacier Bay. I was reminded how back in the days before the ubiquitous camera, people relied on the written word to describe the world around them and their experiences. Muir was a powerfully descriptive writer. Here is one of his passages about Dirt Glacier:

“I greatly enjoyed my walk up this majestic ice-river, charmed by the pale-blue, ineffably fine light in the crevasses, moulins, and wells, and the innumerable azure pools in basins of azure ice, and the network of surface streams, large and small, gliding, swirling with wonderful grace of motion in their frictionless channels, calling forth devout admiration at almost every step and filling the mind with a sense of Nature’s endless beauty and power. Looking ahead from the middle of the glacier, you see the broad white flood, though apparently rigid as iron, sweeping in graceful curves between its high mountain-like walls, small glaciers hanging in the hollows on either side, and snow in every form above them, and the great down-plunging granite buttresses and headlands of the walls marvelous in bold massive sculpture . . .”

He captures the sounds as well:

“Hundreds of small rills and good-sized streams were falling into the lake from the [Stikeen] glacier, singing in low tones, some of them pouring in sheer falls over blue cliffs from narrow ice-valleys, some spouting from pipelike channels in the solid front of the glacier, others gurgling, out of arched openings at the base. All these water-streams were riding on the parent ice-stream, their voices joined in one grand anthem telling the wonders of their near and far-off fountains.”

Muir’s writing captures the exuberance he felt in the sublime natural landscapes. “Standing here, with facts so fresh and telling and held up so vividly before us, every seeing observer, not to say geologist, must readily apprehend the earth-sculpturing, landscape-making action of flowing ice. And here, too, one learns that the world, though made, is yet being made; that this is the morning of creation; that mountains long conceived are now being born, channels traced for coming rivers, basins hollowed for lakes . . .”

Libby: The Alaskan Diaries and Letters of Libby Beaman, 1879-1880. While Muir was off exploring glaciers in southeastern Alaska, Libby Beaman was living with her husband, a government agent supervising the taking of seal pelts on the remote St. Paul Island in the Pribolofs north of the Aleutian archipelago. She was the first non-native American woman to live there, and she accompanied her husband against the wishes of his immediate supervisor and most of her friends and family. America had purchased the Alaskan territory in 1867 for $7.2 million. Beaman calculated that the purchase price was more than recouped in a few years of selling seal pelts. But her husband found the business of taking fur beyond distasteful, and in addition to his unhappiness, Beaman had to deal with his jealousy and an extremely cold, hard winter which bound them to their quarters for seven weeks. She survived that malnourished, suffering from scurvy, but undaunted.

“We find that the winter’s dark and cold are the facts that dominate all life up here. Winter is the event for which everyone spends the other days of the year in preparation.”

Coming Into the Country by John McPhee. McPhee published these essays in 1976, not quite 20 years after Alaska became a state in 1958. In the Statehood Act, the national government promised to transfer to state ownership about a quarter of the land, and over the next 20 years, the fate of the land was debated by groups with conflicting interests: environmentalists and conservationists, oil companies, Natives, and others. In 1971, the Alaska Native Claims Settlements Act awarded about 1/10th of the land and $1 billion to 12 native corporations. McPhee wrote about his impressions of the people, the land of the Brooks Range and the Yukon, Juneau, the debate about where to locate the state capitol and more. He said, “The central paradox of Alaska is that it is as small as it is large — an immense landscape with so few people in it that language is stretched to call it a frontier, let alone a state.” There were about 400,000 people in Alaska in 1976. Current population is still less than 750,000. McPhee writes about how “civilized imagination cannot cover such quantities of wild land,” and how most residents cannot afford the float plane rental to explore or travel in all this wilderness.

McPhee does travel into remote areas. He describes a day on the river in the Brooks Range: “All day, while the sun describes a horseshoe around the margins of the sky, the light is of the rich kind that in more southern places comes at evening, heightening walls and shadowing eaves, bringing out of things the beauty of relief.” Of the tundra he says, “Possibly there is nothing as invitingly deceptive as a tundra-covered hillside. Distances over tundra, even when it is rising steeply, are like distances over water, seeming to be less than they are, defraying the suggestion of effort. The tundra surface, though, consists of many kinds of plants, most of which seem to be stemmed with wire to ensnare the foot. . . . Tundra is not topography, however, it is a mat of vegetation, and it runs up the sides of prodigious declivities as well as across broad plains.” He goes on to say, ” . . . the terrain is nonetheless valuable. There is ice under the tundra, mixed with soil as permafrost, in some places two thousand feet deep. The tundra vegetation, living and dead, provides insulation that keeps the summer sun from melting the permafrost. If something pulls away the insulation and melting occurs, the soil will settle and the water may run off. The earth, in such circumstances, does not restore itself.”

I think it would be fascinating to compare McPhee’s 1970s impressions with the Alaska of today, more than 50 years after statehood. The conflicting interests of environmentalists and oil companies, wilderness advocates and developers, are still raging after all these years.

Chasing Alaska by C. B. Bernard. This memoir of Bernard’s move to Alaska is intertwined with journal entries of an ancestor of his, Joe Bernard, who explored the Arctic and other parts of Alaska 100 years earlier. C. B. Bernard lived in Sitka for two years and he paints a picture of modern life in this Baranof Island town. It rains on average 230 days a year in Sitka, and he says, “Relentless rainfall gives everything the blurry focus of watercolor on paper.” And, “Liquid sunshine, they call the rain here, an intentionally optimistic euphemism, but it’s more like a houseguest who won’t leave or paranoia you can’t shake. Want to survive Southeast Alaska? Learn to ignore rain, or embrace insanity.”

The Woman Who Married a Bear by John Straley. Cecil Younger, a private investigator in Sitka, is asked by an elderly Tlingit woman to look at the evidence in the police investigation of the murder of her son. Though one of his workers was convicted of the crime, the mother wants to understand why he was killed. As Younger starts his case review, he realizes he has stirred a hornets nest and someone has now taken a shot at him. His investigations take him to Anchorage as well. Here are some descriptive scenes from the book:

“Sitka is an island town where people feel crowed by the land and spread out on the sea. This morning to the north and east, the mountains were asserting their presence by showing off the new snow that dusted them down to the two-thousand-foot line.”

“If you live in southeastern Alaska and are used to being stared at by the mountains with your back against the ocean, the country around Anchorage is a reprieve. The horizons are broad and open. The mountains slope up from the tidal flat, cupping Anchorage but not crowding it against the shallow waters of Cook Inlet.”

I found this to be a rather run-of-the-mill mystery novel, and I didn’t like it enough to find other of Straley’s books. But for years I have followed another Alaskan mystery series by Dana Stabenow. Her protagonist is an Aleut woman who lives in a fictional national park in Alaska. If you are looking for Alaskan mysteries, I recommend Stabenow’s.

Two Old Women by Velma Wallis. This is a recounting of a traditional Athabascan tale about two old women who were left to perish by their tribe, which was endangered by the scarcity of food during an extremely cold winter in the region north and east of Fairbanks. Only such dire straits would have compelled the tribe to abandon the weakest members, but the women felt betrayed and decided to die trying rather than wait numbly for the inevitable. They seek to make camp in a place that had been safe in the past, and by snaring rabbits and small game, and drawing on long dis-used skills from their pasts, the women not only survive, but put by surplus food and clothes made of rabbit fur in preparation for the next winter. When their former tribe, still weak and struggling, crosses paths with the women, they share their bounty and regain the respect of the People.

I have read this story several times; once it was a selection for my mother-daughter book group. I love this tale of subsistence — living off the land — and resilient elder women.

The Trap by John Smelcer. This is a wilderness survival tale. Eighty-year-old Albert Least-Weasel is checking his trap lines when he gets caught in one of its steel jaws. As the story unfolds, Albert calls upon his past experiences and traditional stories to survive in the implacable cold. His situation is a race against time as temperatures plummet, the supply of fire wood within his reach diminishes, and hungry wolves scent his growing weakness.

Julie of the Wolves by Jean Craighead George. This juvenile novel won the Newbery medal in 1973. It tells the survival story of Miyax/Julie, a thirteen-year-old who became lost on the tundra after running away from her husband Daniel. She comes upon a den of wolves — four adults and five puppies, and she strives to be adopted into the wolf family, knowing she would starve without their hunting skills. Miyax did have some subsistence and survival skills after living in a seal camp for five years with her Eskimo father. But in the summer’s perpetual day, she did not have stars to navigate by, and she did not know the ways of the tundra birds and animals as she did the coastal ones. Miyax’s father Kapugen told her that the birds and animals all had languages and if you listened and watched them you could learn about their enemies, where their food lay, and when big storms were coming. By mimicking the wolves’ gestures, Miyax is accepted by the alpha wolf, but once the pups are grown, they leave the den, and Miyax/Julie resumes her walk to Point Hope. This is a poignant story about the difficulties of straddling two cultures. Miyax/Julie ultimately wishes to live the Eskimo way, but the law says she must go to school, and the pressures to adapt to modern culture have compromised even her strong father. The book concludes with the words, “the hour of the wolf and the Eskimo is over.”

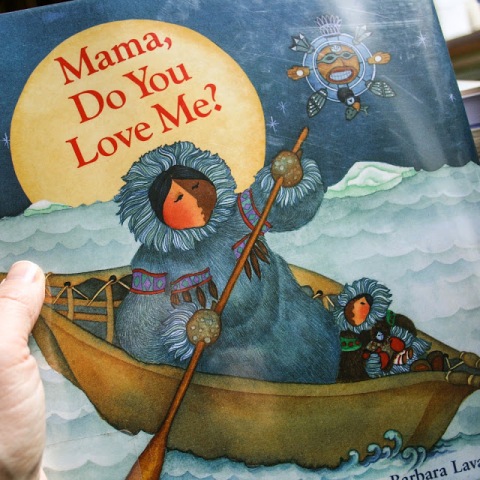

Mama, Do You Love Me? by Barbara M. Joose and illustrated by Barbara Lavallee. In this picture book for young children, an Inuit girl is reassured that her mother will continue to love her no matter what — even if the daughter breaks the ptarmigan eggs, throws water on the lamp, runs away with the wolves, or turned into a musk ox or walrus, etc. I love that the illustrations include Inuit artifacts and Alaskan animals. In fact, I bought a limited edition print of one of the images from this book because I liked it so much.

Reading about Alaska appeals to my sense of adventure. So many of the people live there by intention, drawn by Alaska’s diverse landscapes, the challenges of surviving cold and dark, and any number of individual dreams. These books feed the imaginations of armchair travelers like me.

The next state on my literary journey: Arizona

November 24, 2014 at 9:05 pm

Hi, I’ve nominated you for the One Lovely Blog Award. http://di5lexi.wordpress.com/2014/11/25/awarded-one-lovely-blog/

Thanks for blogging 🙂

November 26, 2014 at 9:14 am

Thank you. I’m honored.

January 31, 2015 at 7:44 am

[…] completed my armchair travels to Alabama and Alaska, I am continuing my literary odyssey with a bookish romp through Arizona. I have actually […]

February 27, 2015 at 2:07 pm

[…] Alaska […]

March 17, 2015 at 6:03 am

[…] from my alphabetical journey across America through books. Having read my way through Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, and Arkansas, today I am making a detour to Nebraska in preparation for an upcoming trip […]